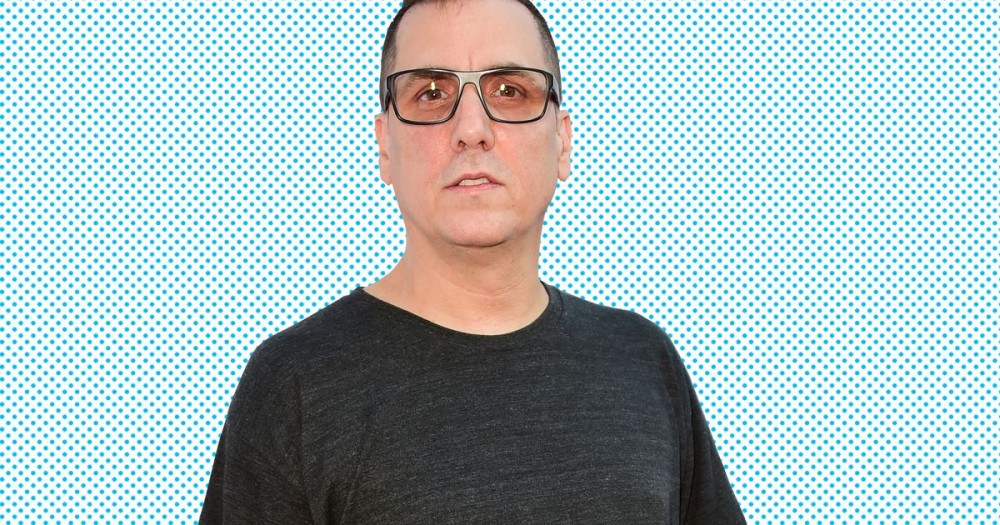

You might know Mike Dean from his work on pivotal Texas rap albums by UGK, the Geto Boys, Z-Ro, and Devin the Dude or from his work as a co-producer, mixer, and masterer for everyone from Kanye West and his G.O.O.D. Music collective to Travis Scott, Frank Ocean, Beyoncé, and Madonna. The Houston native is a gifted guitarist, bassist, and pianist whose instrumental flourishes make a world of difference. The guitar solo in the breakdown during West’s “Devil in a New Dress” catapults My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy into the clouds. The army of keys at the coda of the G.O.O.D. Friday cut “Take One for the Team” gives the song a delightful whiff of Rick Wakeman.

That’s no coincidence, as I learned last week, speaking to Mike Dean on the phone about his tastes and musicianship in anticipation of the release of 4:20, his debut instrumental album. He loves prog rock; the new record makes this plain in the vast, foreboding soundscapes that counterbalance moments more in tune with his hip-hop works. 4:20 is a salute to smokers birthed in the Synth Jam Series Dean began during quarantine in the middle of March. It weaves highlights from five sessions into a 90-minute space odyssey highly suited to soundtrack the holiday it’s named after. As Dean lay low in Studio City, California, he detailed the moment he realized he was sort of making an album, looked back on highlights in a stellar recording career, and detailed the effects of the COVID-19 crisis both on his daily routines and on the livelihood of roadies and crew losing work on lockdown and how he’s helping to ease the burden.

How’s spring treating you, now that everyone is cooped up inside going stir crazy?

I usually don’t leave the house but maybe two or three times a week; I mostly stay at home and order food and groceries, so this is kinda status quo for me.

Did you go in to your livestreams last month with the intention of coming out with a record?

No, not at all. My girlfriend, Louise Donegan, is creative director on the whole thing with me. We were just filming, and after about six or seven nights, I was like, “This is kinda cool. I could chop this up and turn it into something.” For the album, I chose five of the nights, the 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, and 12th. It’s those five days in a row, 18-to-20-minute pieces of music [from each]. And in between each one of those, I put a four-to-five-minute more traditionally produced song. But the rest of the album is really raw. I like that. I didn’t go in and edit and delete bars or layer more stuff. I could’ve overproduced it, but I just wanted it to be exactly what the livestreams were, just mixed well.

I have to admit that when I heard you were doing an instrumental album, I expected massive beats. But this is more like Pink Floyd, Tangerine Dream. I hear a lot of prog rock. What nudged you into that lane?

That’s good you noticed. [Laughs.] That’s what I was going for. I listen to a lot of Pink Floyd. “Welcome to the Machine,” King Crimson, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, stuff like that. That period is my big influence: the synthesizer gods.

4:20, more than a lot of music I’ve heard lately, sounds like the process of music happening. It sounds like a producer playing with LEGOs. How did those live sessions start to come together as an hour-and-a-half experience?

I just reworked my studio, so I have a nice little selection of keyboards in this one corner. Every day I’ll go in there. I’ll do 128 BPMs a day. I’ll pick a key and get the sound I want to start with. I don’t really have anything else planned besides that. I start playing, and it usually works out pretty well. What’d you think of it?

I like it. I saw some people who were like, “I can’t wait to freestyle to this!” I don’t know if they’re going to be able to do that in the way they think. But I love that spaced-out synth stuff that feels like you’re being transported elsewhere.

I did a lot of stuff that’s not supposed to work, really experimenting, and it turns out pretty cool. I’m trying to be the new Philip Glass for this generation. Plus the stuff is very sampleable, I think. There’s so many loops in there.

People are definitely going to make other records out of your record.

That’s half the reason for putting it out. Instead of making instrumental music and pitching it to movies, I just put it up online and let them write to it. I might not go platinum on this album, but I bet 20 things made from it will.

Quarantine is teaching people a bit about how much work can go into one song, especially with the beat battles and fans finding out there’s beats where a person played keyboards, another one did drums, and then someone else worked on lyrics. Have you been following Timbaland and Swizz Beatz’s Verzuz series?

Definitely. I’ve been talking to both of them too.

They trying to get you to do one?

Everybody’s been asking me about that. I would take anybody out, if you can play songs you only played keyboards on like Scott Storch did. He was playing Timbaland beats. If that counts, I can take out anybody. I can just put on Dark Twisted Fantasy and walk away. [Laughs.]

Some producers paint themselves in a corner with a specific sound, but your sound evolves to meet every era. How do you maintain a fresh perspective?

I’ve never tried to chase the last sound. A lot of people get their first hit and go, “This is what’s gonna work, so I’m gonna keep doing this over and over again.” It works, but it gets boring after ten years. A lot of the trap producers who make the same beat over and over, they eventually fade away.

It helps to play a few instruments and have more tools to work with.

Definitely. That’s why I have, like, 50 keyboards. I like to cycle new equipment out of my studio every few weeks. I’ll feature a different keyboard as my main thing for a week or two, until I get bored with it, and then I’ll cycle something else in, instead of how some producers sit there on one keyboard and just use flute sounds. Every keyboard has its own character and personality.

There were OGs to show you the ropes when you were coming up as a musician, and now with your label M.W.A., you’re giving a new generation a shot. How’d you find Apex Martin and everyone?

Apex is a kid from Houston I knew from Twitter. He’d DM me on Twitter and send me beats like, “I’m working at Best Buy. Get me outta here!” Eventually, he sent me some stuff that I liked, so I signed him to a publishing deal. He’s actually bringing me projects now, which is good. He brought Roddy Ricch recently; we did a song with him. He brought me the Smokepurrp album.

You met Kanye West mixing Scarface’s “Guess Who’s Back,” which he produced, and you’ve been working with him ever since. What is it about your individual styles that makes the two of you a good creative match?

We’re both a little bit crazy. We push each other really hard to make each other better. From the first music we worked on — “Through the Wire,” “Keep the Receipt,” stuff that was on the first mixtapes that he put out — every time he’d come to my house in Texas, I’d be like “So, what are you gonna do next?” I’d kinda give him a little push.

One of my favorite moments on a Kanye and Mike Dean record is the guitar solo on “Hold My Liquor.” What inspired that? It sounds like Judgment Day.

Justin Vernon [of Bon Iver]. The setting on the guitar for the harmonizer part that makes it sound crazy is what he had on his voice for that song. Me and Justin made that song in Paris. I played the chords on the Memory Moog, and he sang the chorus. Then I turned it over, and everybody added onto the beat. After we thought the song was done, I went home and I was fucking around, playing guitar along with it, like, “Let me try these vocal presets on the guitar.” That’s where the solo came from. I was just screwing around. I played an eight-minute guitar solo and sent it to Kanye, and he threw it on the album.

Let’s go back to Wyoming, 2018. Was it tough getting five records out back to back in just over a month?

It’s the pace we work at, but those albums … Kanye was more involved with some of ’em than others, and I was more involved with some of ’em than others. A couple of those would be coming out on Thursday, and Kanye would leave on Tuesday, like, “Okay, Mike, you finish it.” I think after Pusha-T and the Ye album, he would finish his vocals and be like, “Peace, I’m out. You mix it and do what you gotta do.” And me and the whole crew would stay in the studio and finish it. We learned that work flow from the G.O.O.D. Friday shit, I think, putting out a song every Friday. We learned how to prepare a song in four hours.

What was your favorite G.O.O.D. Friday track?

Maybe “Take One for the Team.”

Is there a plan to put the G.O.O.D. Friday songs on the streaming services the way people are rereleasing older mixtapes now?

They’ll be out someday. Maybe on the tenth anniversary [in August]. I was trying to do it last year, but it was too late. They’ll probably end up on Tidal or something.

People will definitely be looking now! Last year you mixed the Sunday Service album, Jesus Is Born. The voices on that one cut like a sword. Was it different working with gospel?

It’s hard not to make a hundred people cut, you know? That album was mixed really fast, in two, three days. That’s why it’s so cohesive; the faster you mix, the more they sound cohesive. One cool thing about that — where was the place in the desert where he took the choir, the big dome?

Roden Crater, where they shot the movie?

The crater had this tunnel that’s based on a flute. It’s the same dimensions as a giant flute, a few hundred feet long. That was the echo and the reverb that made the vocals in the movie sound cool. For the album, I digitally recreated the sound of that tube.

Is there a plan to release the movie? I caught in the theater, but I don’t know if everyone who wants to see it has seen it.

That’s the thing about Kanye. He makes great movies and never releases them.

Everyone is still waiting on the Yeezus movie.

They’re still waiting on Cruel Summer. I saw Cruel Summer in Cannes.

Did reworking the Yandhi songs for the Jesus Is King album surprise you at all?

Nothing’s surprising with Kanye.

This is a scary time for people who work anywhere in music. Without being able to play shows and get out places …

All the crews, all the roadies, sound guys, programmers, lighting guys are all fucked. For every Kanye or Travis Scott, there’s hundreds of people that are out of work.

What are your plans for the spring after 4:20?

Just the standard: Travis Scott, Kanye, Kid Cudi. We’re all working on a little stuff here and there. Nothing real concentrated.

Speaking of 4/20, indica or sativa?

Indica.

Joints or blunts?

Joints. I quit smoking tobacco like three months ago, so I haven’t had a blunt in three months.

I feel like everyone is using this time as a reset. What else has changed for you?

After Kobe died, I tweeted that everybody needs to slow down. The whole world is going way too fast for me. Too much crazy shit happening. Pollution destroying the world. Global warming. [The pandemic] is changing that. You walk outside and look at the sky, and there’s no chemtrails. You can see the mountains in California. Usually you see a haze. It’s beautiful. It hasn’t looked like this here for 20 years. It’s like the world needed an enema.